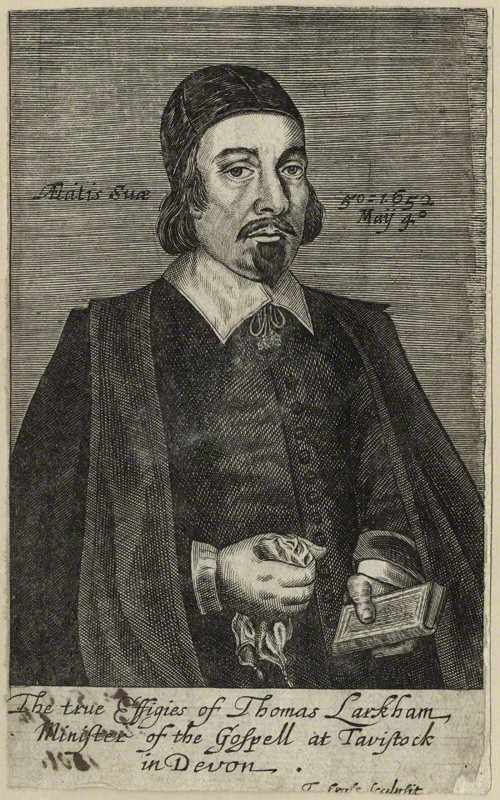

Reverend Thomas Larkham |

||||||||||

of Tavistock, England | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

8) ANE

LARKHAM was baptized 14 June 1635 at Northam, Devon, England[20].

She died on 18 November 1635.

|

Possibly Thomas Larkham | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

Referred to

varyingly as “one of the stormiest petrels of a stormy era”[21]

and “a Man of great Piety and Sincerity”[22],

much has been documented of the life of Thomas Larkham of Tavistock, most

recently by Susan Hardman Moore in her excellent edition of his diary,

The

Diary of Thomas Larkham, 1647-1669.[23]

In the introduction, Hardman Moore writes, “Thomas Larkham

is long dead, but lives on in Tavistock folklore with a divided reputation.

For some, he is a rascal vicar who turned religious life upside down in

Cromwell’s time. For others he is something of a hero, founder of the

Christian community which today is Tavistock United Reformed Church. … Up in

Cumbria too, Cockermouth URC remembers Larkham and takes pride in its

history: a banner over the church gate is emblazoned with the date of its

foundation, ‘1651’. The Tavistock and Cockermouth URC congregations

are two of only a handful in England which have a continuous history from

the ‘parish congregationalism’ of the 1650s. Thomas Larkham pioneered both

these local reformations.”[24] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

The Early Years 1602-1626 | ||||||||||

|

Thomas Larkham was born at Lyme Regis, “the Pearl of Dorset”, a small seaport town in West Dorset, England in the final year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. He was the eldest of four children born to Thomas and Jane Larkham. Little is known of Larkham’s early life. He was born into the mercantile class, as his father described himself as a “linen draper”[25], a merchant of cloth made of flax and hemp. Lyme Regis became a major English port during the 16th and 17th centuries, so it’s possible the elder Larkham was engaged in trade in the Mediterranean, West Indies and Americas.[26] Thomas Larkham’s parents had means to provide their son with an education, and he entered Cambridge at the age of nineteen, where he took his B.A. from Trinity Hall in 1621-1622. On 10 June 1622, he married Patience Wilton after the birth of their first child, Thomas, who was baptized at Crediton on 16 March 1622.[27] The wedding took place at the Parish Church of Shobrooke. Patience Wilton was the daughter of George Wilton, a well-to-do[28] schoolmaster at Crediton. Larkham was not yet 20 years of age and she was six years his senior.[29] On 25 September 1625, Larkham was appointed Chaplain of the Sandford Chapel in Crediton, and licensed as preacher throughout the dioceses of Exeter, London, and Bath and Wells.[30] Larkham took his M.A. from Cambridge in 1626.

Two more children

of Thomas and Patience Larkham were born during this time, a son, John,

baptized 10 October 1624 who died in infancy on 7 July 1625, and a

daughter, Patience, baptized on 26 February 1625.[31] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Vicar of

Northam 1626-1640 | ||||||||||

|

Larkham was ordained Vicar of Northam, near

Bideford in north Devon, on 26 December 1626, a position he held for the

next thirteen years. Five more children were born to Thomas and

Patience Larkham at Northam, two of whom survived early childhood. A

son named William was baptized on 8 June 1628 and died at 4 ½ years of age

on 25 January 1633; son George (probably named for his maternal grandfather,

George Wilton) was born 20 April 1630 and baptized 2 May 1630; daughter Jane was baptized

11 February 1631; an infant son was

baptized 10 November 1633 and probably died in infancy; and a daughter, Ane

(or Anne) was baptized 14 June 1635 and died in infancy on 18 November 1635.[32]

In

Northam, Larkham’s religious views on church sacraments and mandatory tithes

were considered controversial and they eventually got him into trouble.

A petition was circulated against him by his detractors and in 1639

“delivered into the king's own

hand, with 24 terrible articles annexed, importing faction, heresie,

witchcraft, rebellion, and treason.”

He claimed he was “put into Star-chamber and

High Commission,” and was proceeded against in the Consistory Court at

Exeter “under a suit of pretended slander for reproving an atheistical

wretch by the name of Atheist.”[33] It’s believed Larkham

left with his family for New England

before 19 January 1640 when the next

Vicar of Northam was appointed.

Certainly, he was absent from England by April 1640. His father, whose

will was written 29 August 1638, died in early 1640.

[34] The will

was proved and administered 8 April 1640 by Thomas’ younger brother Michael Larkham

following the “renunciation of the executorship of Thomas Larkham”[35] | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

New England 1640-1642 | ||||||||||

|

In New England, Larkham

went first to Massachusetts,

“but not being willing to submit to the discipline of the churches there,

came to Dover, a settlement on the river Piscataquis, Maine

(now New Hampshire)”.[36]

Dover was renamed Northam after Larkham’s vicarage in England.

During his two years in New England, his ideas

were considered controversial and he developed a tempestuous relationship

with the local minister, Hansard Knollys, whom he ousted. Larkham

“received all into his Church, even immoral

persons, who promised amendment. He baptized any children offered, and

introduced the Episcopal service at funerals.”[37]

Larkham was outspoken and voiced his opinion on religious and civil matters

to which he disagreed. This led to great discontent and even outright

physical fighting with Knollys and his followers, as recounted by Belknap: “…

[Knollys] excommunicated Larkham.

This bred a riot, in which Larkham

laid hands on ·Knollys, taking away his hat on pretence that he had not paid

for it; but he was civil enough afterward to return it. Some of the magistrates

joined with Larkham, and forming a court, summoned Underhill, who was of

Knollys's party, to appear before them, and answer to a new crime which they

had to allege against him. Underhill collected his adherents: Knollys was

armed with a pistol, and another had a bible mounted on an halbert

[halberd or pikestaff]

for an ensign [banner].

In this ridiculous parade, they marched against Larkham and his party, who

prudently declined a combat, and sent down the river to Williams, the

governor, at Portsmouth, for assistance. He came up in a boat with an armed

party, beset Knollys's house, where Underhill was, guarded it night and day

till a court was summoned, and then, Williams sitting as judge, Underhill

and his company were found guilty of a riot, and after being fined, were

banished the plantation. The new crime which Larkham's party alleged against

Underhill was, that he had been secretly endeavoring to persuade the

inhabitants to offer themselves to the government of Massachusetts, whose

favor he was desirous to purchase, by these means, as he knew that their

view was to extend their jurisdiction as far as they imagined their limits

reached, whenever they should find a favorable opportunity. The same

policy led him with his party to send a petition to Boston, praying for the

interposition of the government in their case.”[38]

Commissioners from Boston were sent to arbitrate

and they found both parties at fault. Governor John Winthrop of the

Massachusetts Bay Colony was particularly critical of Thomas Larkham and

even validated allegations that he fathered an illegitimate child with his

housekeeper.[39]

(No record of the birth of this child can be found. Some sources state

Larkham admitted to be the father, a statement for which there appears to be

no verification. Possibly the allegation was politically-motivated.)[40]

Larkham departed New England for England with

his eldest son Thomas on 14 November 1642, leaving behind his wife and

three younger children. He later described them

“as dry bones[41]

and diverse years after; yet did the Lord bring them altogether again here

in England.”[42],

[43] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Return to England 1643-1645 | ||||||||||

|

Mrs. G.H. Radford

suggests Larkham and his son returned to England

“from

Portsmouth, N.E., to Madeira, and there found a ship to bring them to

England”.[44]

In the paper she wrote on Larkham, read at Plymouth July 1892, she states, “In what ship Larkham and his son embarked is not certain, nor whither she was bound, but it is a curious coincidence that the paragraph after that relating Larkham’s downfall in Governor Winthrop's History, speaks of the arrival ‘at Boston of a small ship from the Madeiras with wine, sugar, etc., which were presently sold for pipe staves and other commodities of the country, which were returned to the Madeiras, but the merchant himself, one Mr. Parish, said divers months after. The passage[45]

connecting Larkham with the Madeiras is as follows: ‘With his index expurgatoris (a trick which

perchance he learnt of the Jesuites in Medera [sic] when New England was too

hot for him), no less than four of our names which subscribed the reply he

expungeth at a clap’ etc.”[46] Larkham is next found in the records at East

Greenwich, Kent, on May 31, 1645. The report of the “Committee for

Prundred Ministers” records the following complaint about Larkham by the

local minister, Mr. Spratt, “Whereas the Vicarage of the Parish Church at

East Greenwich, in the County of Kent, is and standeth sequestered by order

of the Committee, from Dr. Creighton to the use of Thomas Spratt, a godly

and orthodox divine, and complaint is made into this Committee that one

Thomas Larkham intrudeth himself into the said Church to preach there,

against the consent of the said Mr. Spratt and without any order. This

Committee doe hereby inhibit the said Mr. Larkham from his said preachinge

there as aforesaid, and doe require him to forbeare any further to disturbe,

molest, or interrupt the s’d Mr. Spratt in the discharge of the duties of

the s’d place according to the s’d sequestration.”[47]

The complaint was resolved by allowing Larkham

to preach on Wednesday and Thursday afternoon, and Mr. Spratt would preach

in the morning.

Larkham’s son Thomas

possibly met his wife, Mary Covert, during this time in East Greenwich. It’s

known from Larkham’s diary that Mary Covert had a brother or cousin, Richard

Covert. A Richard Covert is named as son and executor of the will of

Richard Covert “of East Greenwich, Kent, Citizen and Merchant Tailor of

London”, written August 28, 1638 and proved August 30, 1645.[48] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Chaplain in Sir Hardres Waller’s Regiment of the

Parliamentary Army 1646-1649 | ||||||||||

|

Soon thereafter,

Larkham accepted an appointment as chaplain in Sir Hardres Waller's regiment

in Cromwell’s Parliamentary Army. The regiment went to

Ireland. Hardman Moore suggests “Larkham’s wife and

family may have stayed at Crediton while Larkham (and his son-in-law Miller)

served with the parliamentary army. Larkham’s will, 1669,

mentioned ‘my mansion house at Crediton’”.

[49]

Larkham’s daughter, Patience, married Lt. Joseph Miller[50]

who also served in the Parliamentary Army. Their son

Thomas was born at Crediton on June 9, 1648.[51]

Of this appointment,

Larkham stated that he was “chaplain to one of greatest honour in the

nation, next unto a king, had his residence among ladies of honour, and was

familiar with men of greatest renown in the kingdom, when he had a thousand

pounds worth of plate before him.”[52]

It was during this

time that his eldest son, Thomas died in the East Indies[53].

In his diary, he wrote,

“Thomas mine Eldest

sonne Died Feb 14th 1648 & left [M]ary his wife ^a widdow^ & one

sonne & one daughter viz Thomas & Mary”[54]

Little is known of

Mary Covert. It’s assumed that she and her daughter Mary

died shortly the death of Larkham’s eldest son. The

grandson, Thomas “Tom”, referred to by Larkham as an orphan, came to live

with his grandparents after 1648, and was raised by them.

There are many entries in Larkham’s diary about his grandson.

Larkham was dismissed

from his appointment as chaplain of Waller's regiment on 15 November 1649.

In his diary he states he had “differences about their irreligious

carriage.” It’s believed he was dismissed

following a court-martial, in which he was found guilty of inciting to

insubordination. He appears to have secured another military post, because he wrote of receiving money in 1651 at a

“muster in Carlisle for my men;” and on

11 June 1652 he received

eleven days' pay from Ebthery at Bristol, “they being about to take

ship,” perhaps for Ireland.[55] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Vicar of Tavistock 1649-1664 | ||||||||||

|

Larkham came to

Tavistock in April 1647-48 with the Parliamentary Army, where Sir Hardres

Waller had his headquarters. The vicarage of Tavistock

had been vacant since October 21, 1643 when the prior vicar left for

Plymouth. It is presumed that Larkham succeeded to the Tavistock vicarage

before 1649 because the report by the commissioners visiting Tavistock on

October 18, 1650 noted that Larkham was elected by the inhabitants and

presented by the Earl of Bedford, 'who as successor to the abbey held all

the great tithes and the right to present.'

It wasn’t long before conflict broke

out as a result of Larkham’s opinions on tithes and administering of the

sacraments. He referred to his critics as ‘profane

ones’, who ‘gnash their teeth to see Christ’s ordinances on foot in

public, and themselves laid by as reprobate silver; they began to quarrel at

my preaching and to join shoulder to shoulder against the new Church (as

they were pleased to call us…)”.[56]

As tension increased with his detractors, in 1651, Larkham departed

with his son George, recently graduated from Oxford, on a trip north to

Cumberland. The Larkhams were warmly received at Cockermouth where

Thomas Larkham was hailed as a ‘blessed instrument of God’. He

shepherded the formation of a new church in fall 1651, with George Larkham

and George Benson, Vicar of Bridekirk, as founding members.[57] In 1652, Larkham made his way back to Tavistock having received a

letter from more than sixty people from the congregation there pleading for

his return. George Larkham stayed at Cumberland. When Larkham

arrived back in Devon, he learned his enemies had locked him out of the

church.[58]

He wrote in his diary, “Thus farre the Lord hath holpen me and hath delivered me from

all my fears, troubles and dangers. By him I have leaped over many walls and

have skipped over many craggy mountains. I remember thy great name in

England and thy poor despised handful in Tavistock. This present first of

June I write these lines. This day twelve month I had the doors of the

parish church shutt up against me by Hawsnorth, a sad trooper in the Kings

army, chosen the Saturday before to be churchwarden, and confirmed by

Glanville and others. I have been this year exceedingly persecuted by

arrests, in the Committee for plundered ministers, by enditement for a

supposed Riott with divers of my brethren to the expense of at least £50

charges. Yet, out of all the Lord hath delivered me; blessed be his name.”[59]

A Full Household While at Tavistock, there were many diary entries

of the concern, love and affection Larkham bore his children and

grandchildren. At a time when his children had married and were

raising families of their own, tragedy put Larkham in the role of caregiver

once again in his 50s. Larkham’s grandson, Tom Larkham (son of his

eldest son Thomas who died in the East Indies in 1648) was living in

Tavistock with his grandparents by April 1650, having been orphaned by both

parents by this date. Tom Larkham, probably born between 1645 (Larkham

and his son arrived in East Greenwich in 1645) and 1647 (his father died

February 14, 1648 in the East Indies) was raised by his grandfather.

This was not always an easy calling for Larkham. On August 18, 1654, Thomas Larkham wrote of his

grandson, who was probably between 7 and 9 years of age: “This very Day August 18th 1654

There was a trial in the court of Tavistocke betweene Thomasin Smith and my

grandchild Thomas Larkham for driving and beating her Sow[.] It was God’s

pleasure for ends best knowne to his Wisdome to suffer me to be foiled in

this action &c[.] With this fatherly Whip beginneth the three & fiftieth

yeare of mine age. But my hope is that His holy Majesties s[h]all

bringe good out of this afliction and all others which mine unworthy

walking have caused his fatherhood to lay uppon me. But the deriding

of thy Church, waies and Worship by Everleigh the steward of the court &

others O Lord forget not. Hallowed be thy name.”[60] The husband of Larkham’s daughter, Patience, died

in Ireland May 8, 1656. Larkham wrote in his diary, “Joseph Miller Lieutenant in Ireland Died May

the 8th 1656 & left mine eldest daughter Patience ^a widow^ & one

son & 3 daughters living viz Thomas, Mary, Jane, and Anne”[61] A month later, he wrote: “June 21, Saturday My Eldest daughter Patience Miller came to my house at Tavistock from Ireland a widow, D.G / D,M”[62] While this initial visit was temporary, by fall

1656, Patience Miller and her two of her children, Thomas and Jane, were

living in Tavistock with the Larkhams and their grandson Tom. The two

young cousins, Tom Miller and Tom Larkham were close in age and possibly

more like brothers. This relationship would factor significantly later

in their lives.[63]

Their grandfather Larkham was likely a key influence in the lives of his two

fatherless grandsons as a role model and provider. While Larkham

clearly reared young Tom Larkham, his diary ledger indicates that he also

contributed significantly to the upbringing and schooling of Thomas Miller. With a household including himself, his wife, his

grandson Tom, his daughter Patience and her children Thomas and Jane, by

September 1656, Larkham was anxious about the family members’ dependence

upon him: “And nowe Righteous Father I come unto thee in

my greate distresse and troubles. I have A family to care for

consistinge of sixe persons with My Daughter Patience and her sonne 2 poore

Sisters of Mine expect helpe whom I have often holpen heretofore & would now

againe.”[64]

Scurrilous Pamphlets By 1657, Larkham’s relationship with his

religious opponents had escalated and become public. He attacked his

adversaries in a tract entitled ‘Naboth, in a Narrative and Complaint

of the Church of God at Tavistock, and especially of and concerning Mr.

Thomas Larkham.’ The five parishioners on which the tract was

targeted responded in “The Tavistock Naboth proved Nabal: an Answer to

a Scandalous Narrative by Thomas Larkham, in the name, but without the

consent, of the Church of Tavistocke in Devon, etc., by F. G., D.

P., W. G., N. W., W. H., etc.’[65] In their response, the parishioners denounced

Larkham's affection for sack (fortified wine) and bowls (a form of lawn

bowling), alluded to his published attacks on tithes, and revived the

allegation of immorality in New England Larkham. Larkham referred to

this as ‘a heape of trash, full fraught with lies and slanders.’ He

countered with a pamphlet called ‘Judas Hanging Himself,’',

and his enemies countered back with ‘A Strange Metamorphosis in

Tavistock, or the Nabal-Naboth improved a Judas’.[66]

A weekly lecture was established in Tavistock by

Larkham’s rivals in October 1659, at which nearby ministers officiated.

Despite his resistance, the council of state ordered the justices living

near Tavistock to continue the lectures, and to question witnesses regarding

the alleged crimes and misdemeanors against Larkham. Following the trial on

April 17th, Larkham was ordered to allow others to preach in the

parish church. The justices met on October 19th to determine whether Larkham

had been legally appointed to the vicarage of Tavistock. On Sunday October

21st Larkham resigned the benefice. Despite this, he was arrested

on January 18, 1661, and he spent eighty-four days in prison at Exeter.[67] On this date, he wrote in his diary: “I was made a prisoner by Col. Howard and had a guard of six

soldiers put into my house, and the Monday following was conveyed by sixty

troopers to the Provost Marshall at Exeter, and returned not until April 11th.

Eighty four days in all. Divers men and women sent tokens of their love to

me, the which I wrote out and cannot now find. The Lord grant that it may be

for the furtherance of their profit and abound to their account

respectively. Thou Lord knowest them by name and what they did in the way of

communicating with mine affliction."[68] Following his release from prison, Larkham

returned to Tavistock to live with his daughter Jane and son-in-law, Daniel

Condy.[69]

The Act of Uniformity and the Great Ejection

of 1662 On May 19, 1662, the parliamentary Act of

Uniformity was enforced. The act prescribed the form of public

prayers, administration of sacraments, and other rites of the Established

Church of England, following all the rites and ceremonies and doctrines

prescribed in the Book of Common Prayer. More than 2,000 clergymen,

including Thomas Larkham and his son George, refused to take the oath and

were ousted from the Church of England in what became known as the Great

Ejection of 1662. This created the concept of non-conformity, with a

substantial section of English society excluded from public affairs for well

over a century. Thomas and George Larkham were among the

“nonconformists”.[70] On August 18, 1662, the deadline to subscribe to

the Act of Uniformity, Larkham wrote in his diary: 1662 August the Eighteene beginneth

the one and Sixtieth yeare of mine age The saddest weeke that England

ever saw Witnesses slaine by virtue of a

Law. Many fall off in this sad day

of trial, God’s cause meets now with many

a deniall. All proved not gold that

glister’d and was specious, All are not found to have that

faith that’s pretious. Yesterday ended Godly men’s

preaching That do refuse traditions of

men’s teaching. Enter the Mattins of

Bartholomew Lord keepe thy poore saints

from the bloody crew. Let not the cruell make it

suche a day as ‘twas in 72 O Lord I pray. Bury in Christs grave sinnes

with his dolours Reduce poore souls that have

fled from their colours Lord make amend of this sad

dismall story, And let thy praying people see

thy glory.[71] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Tavistock Apothecary 1664-66 | ||||||||||

|

In 1664 Larkham left the ministry and became a

partner with Dr. Peter County, an apothecary and physician in Tavistock.

Larkham successfully carried on the practice after Dr. County's death[72]

with the help of his grandson, Thomas Miller, who came to Tavistock on

October 26, 1664 to help with the apothecary shop[73]

and his daughter Patience.[74]

By May 29, 1665, Larkham learned of his

excommunication: “This day it was

told me that yesterday the 28th of May yong Preston of Maritavy

officiating at Tavestocke pronounced me Excom: by authoritie from yong

Fulwood now Ar[ch] Deacon at Totnes. Consider O Lord these fooles and

pitty them for they know not what they doe. Suffer not thy greate name

to be (SO) taken in vaine.[75] The Five Mile Act of 1665 In October 1665,

the Five Mile Act, or Nonconformists Act 1665, was passed. The act

forbade clergymen identified as nonconformists from living within five miles

(8 km) of a parish from which they had been expelled, unless they swore an

oath never to resist the king, or attempt to alter the government of Church

or State.[76]

Once the act was in force, Larkham was prevented from staying in Tavistock.

He gave up the apothecary shop on January 18, 1666 (1665/66).[77] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

His Final Days 1666-69 | ||||||||||

|

According to the Tavistock Congregational Church, “Mr Larkham was suffered peacefully to preach under the very

shadow of the church he had left, protected by the powerful influence of the

house of Russell[78].

He was at one time threatened with imprisonment if he went beyond his own

house but the threats were never put into execution.”[79] By this time his grandsons, Tom Larkham and Tom Miller were

frequently abroad, involved in trade in the West Indies, Virginia and the

Carolinas. When he wrote his will on June 1, 1668, he mentioned that

Tom Larkham had recently returned from Barbados. Thomas Miller, was involved

in the tobacco trade in Virginia and later in Albemarle, Province of

Carolina. In his diary Larkham wrote: “Where[a]s I laid out about freeing of

Tobacco for T. M. (Thomas Miller) and for charges about bringing it to

Tavistocke 13. 17. 04. I have received for Tobacco & the caske

in which it was brought from Virginia 141i. 01. 03.”[80] In August 1668, Larkham once again moved in with his daughter and

son-in-law, Jane and Daniel Condy. His final entry in his diary, dated November 17, 1669, was for his

customary sixpenny trim at the barber, one month before his death on

December 20, 1669.[81]

His burial on December 23, 1669 was recorded in the Tavistock Register: “Burials December 1669. 23 Mr

Thomas Larkham buried.”[82] Of his burial Edward Windeatt wrote, “It would seem that an attempt was made to prevent his burial in

the church; but the steward of the Earl of Bedford interfered, and he was

buried in the part of the chancel which belonged to the house of Russell.”[83] Thomas Larkham’s will was written 1 June 1668

and proved 9 March 1669. He names his son George Larkham “mine only son living late a publique preacher” to whom he bequeathed

“all my land and right of reversion in them both at

Crediton and Tavistock”; his grandson Thomas Larkham “son of my

eldest son who is lately returned from the Barbados who hath

been very chargeable to me from the time of his birth and by the

unkindnesses and bad dealing of his mothers relations and his

miscarriage which I hope he begineth to see and yet dare not be

too confident of him for the time to come”

to whom he bequeathed “my best silver bowle and my ring which hath my

seal in it”; his grandson Thomas Condy to whom “if he be a student”

he bequeathed “at least one third part according to their valuation

by indifferent men, of my said books”; his wife Patience to whom

he bequeathed “the rent of Mills in Dolvin during her life if she

lives so long live, but if she outlive them

she shall be maintained by the rents of my lands, but if she dies, the

lives continuing, the annuity shall be divided between my two

daughters Patience and Jane” and “Residue to use my

wife while she liveth and after to be divided

between the children of my

children equally everyone a little as far as it will reach, with

my blessing on them and it.”; his daughter Jane; his

daughter Patience “my undone daughter” to whom he bequeathed “My

apothecary ware and utensills” provided the bequest “be

managed by George Larkham my son and Daniel Condy my

son in law both or either of them for and her use that her

husband may not have the wasting of it as he hath of the rest of her

estate and I desire my son and son-in-law to be instead of

a father friend and husband to her and her poor children that shall be

living after my death or such of them as they think fit objects for

their help: if any of them prove lewd, let them be cast off”; and

his son-in-law Daniel Condy.[84] The works of Thomas Larkham include: 1.

‘The Wedding Supper,’ l2mo,

London, 1652, "with portrait", engraved by T. Cross. Dedicated to the

parliament. 2. ‘A Discourse of Paying of Tithes by T.

L., M.A., Pastour of the Church of Tavistocke,’ 12mo, London, 1656.

Dedicated to Oliver Cromwell 3. ‘The Attributes of God,' &c.,

4to, London, 1656, with portrait, British Museum. Dedicated to the fellows,

masters, and presidents of colleges, &c., at Cambridge.

[85]

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Notes | ||||||||||

|

[1]

"England, Marriages, 1538–1973," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/N2LT-XZW : accessed 05 Sep

2012), Thomas Larckham and Patience Witton, 20 Jun 1622; citing

reference , FHL microfilm 916934.

[2]

"England, Births and Christenings, 1538-1975," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/J367-5M6 : accessed 05 Sep

2012), Patience Wilton, 14 Apr 1594; citing reference , FHL

microfilm 917182.

[3]

"England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/N591-68L : accessed 05 Jul

2014), Thomas Larcombe in entry for Thomas Larcombe, 16 Mar 1622;

citing Crediton, Devon, England, reference ; FHL microfilm 917182.

[4]

Thomas Larkham and Susan Hardman Moore, The Diary of Thomas Larkham:

1647 - 1669. (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2011.) 33.

[5] Parish

register transcripts, 1630-1837 Church of England. Parish Church of

Sandford (Devon)

[6]

Parish register transcripts, 1630-1837 Church of England. Parish

Church of Sandford (Devon)

[7]

Thomas Larkham and Susan Hardman Moore, 286, and 286, note 1.

[8]

Transcripts of parish registers and Bishop's transcripts, 1609-1837

Church of England. Parish Church of Highweek.

[9]

Items 2-3 Parish register transcripts, 1538-1836 Church of England.

Parish Church of Northam (Devonshire).

[10] Transcripts of parish

registers and Bishop's transcripts, 1609-1837 Church of England.

Parish Church of Highweek.

[11] Items 2-3 Parish register

transcripts, 1538-1836 Church of England. Parish Church of Northam

(Devonshire).

[12] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore. 174. “Aprill 20th I called

to mind the birth of my dear son George on this day in the yeare

1630…”

[13] Parish register transcripts,

1538-1836 Church of England. Parish Church of Northam (Devonshire)

[14] The register of Bridekirk,

1584-1812 Church of England. Parish Church of Bridekirk

(Cumberland).

[15] "England, Births and

Christenings, 1538-1975," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/JWJX-PBZ : accessed 06 Sep

2012), Dorothea Fletcher, 30 Oct 1633; citing reference , FHL

microfilm 0924748 IT 1.

[16] "England, Births and

Christenings, 1538-1975," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/JWXB-JRZ : accessed 06 Sep

2012), Larkham, 11 Feb 1631; citing reference , FHL microfilm

917204.

[17] The Western antiquary, Volume

8. Editor, William Henry Kearley Wright. Publisher, Latimer & son,

1889. Original from, Princeton University, 171.

[18] Mrs. G.H. Radford, "Thomas

Larkham." Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association

for the Advancement of Science, Literature, and Art. Vol. XXIV.

(Plymouth: William Brendon and Son, 1892.), 122.

[19] Parish register transcripts,

1538-1836 Church of England. Parish Church of Northam (Devonshire)

[20] Parish register transcripts,

1538-1836

[21] Charles Knowles Bolton,

The Founders: Portraits of Persons Born Abroad Who Came to the

Colonies in North America before the Year 1701. (S.l.:

Boston Athenaeum, 1919.) 787.

[22] Edmund Calamy, Samuel Palmer,

Thomas Gibbons, James Caldwall, and William Harris,

The

Nonconformist's Memorial:: Being an Account of the Ministers, Who

Were Ejected or Silenced after the Restoration, Particularly by the

Act of Uniformity, Which Took Place on Bartholomew-Day, Aug.24,

1662. Containing a Concise View of Their Lives and Characters, Their

Principles, Sufferings, and Printed Works. (London:: Printed for

W. Harris, No. 70, St. Paul's Church-Yard., n.d.) 79.

[23] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore. See Note 4 for full citation.

[24] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 29.

[25] Grant of Administration,

Will, 1640, Thomas Larkham, Linen Draper, /Lyme Regis/Dorset.

Wiltshire Council. Probate Records of the Court of the Dean of

Salisbury, n.d. Web. 05 July 2014.

<http://history.wiltshire.gov.uk/heritage/getwill.php?id=109704>.

Reference Number P5/13Reg/221B

[26] Larkham’s diary infers that

he was involved in overseas trade, as was his son Thomas and his

grandsons, Tom Larkham and Thomas Miller. Larkham’s eldest son,

Thomas died while in the East Indies in 1648. Mrs. G.H Radford

speculates he may have been there “possibly with some Dutch

friends on a trading venture”. (Mrs. G.H. Radford, p. 107) Mary

Covert, the wife of Thomas Larkham, the son, was likely of Dutch

decent (the surname Covert has Dutch origins). Larkham’s grandson, Tom Larkham, travelled to Barbados several times; a few trips were referred to in Larkham’s diary and will. Another grandson, Thomas Miller, traded in tobacco in in Virginia and later in Albemarle, Province of Carolina. In his diary Larkham wrote: “Where[a]s I laid out

about freeing of Tobacco for T. M. (Thomas Miller) and for charges

about bringing it to Tavistocke 13. 17. 04. I have received for Tobacco & the

caske in which it was brought from Virginia 141i. 01. 03.” In October 1657, Larkham noted in

his diary, “I was deceived in Tobacco which cost 2[£]-00-0.”

(page 161). Hardman Moore suggests “Perhaps this was an earlier

[trade] venture which went wrong.”

[27] The parish records of

Crediton, Devon, England contain a baptism record of Thomas

Larcombe, son of Thomas Larcombe, on March 16, 1622. See note

3.

[28] Mrs. G.H. Radford, 96.

[29] "England Births and

Christenings, 1538-1975," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/J367-5M6 : accessed 05 Jul

2014), Patience Wilton, 14 Apr 1594; citing Crediton,Devon,England,

reference ; FHL microfilm 917182.

[30]

"Larkeham, Thomas (1623 - 1641)." The Clergy of the Church of

England Database 1540-1835. Ed. Arthur Burns, Kenneth Fincham,

and Stephen Taylor. King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS,

England, United Kingdom. Oct. 1999. Web. 05 July 2014.

<http://db.theclergydatabase.org.uk/jsp/persons/CreatePersonFrames.jsp?PersonID=71334>.

[31] Dictionary of National

Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 32, 151

[32] "England Births and

Christenings, 1538-1975," index, Larkham, Northam, Devon, England,

Reference; FHL microfilm 917204.

[33]

Sydney

Lee, ed. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume

32. (New York: McMillan, 1892),

151.

[34] Sydney Lee, 151.

[35] Mrs. G.H. Radford, 100.

[36] Dictionary of National

Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 32,151.

[37] Joseph B. Felt,

The

Ecclesiastical History of New England Comprising Not Only Religious,

but Also Moral, and Other Relations. (Boston: Congregational

Library Association, 1855.) 451.

[38] Jeremy

Belknap and John Farmer. The History of New Hampshire. Dover:

S.C. Stevens and Ela & Wadleigh, 1831. Print.

[39] John

Winthrop, Winthrop's Journal: "History of New England”,

1630-1649. Ed. James K. Hosmer. (Reprinted. The University

of Michigan: C. Scribner's Sons, 1908.) 88-89. “Mr. Larkam of Northam, alias

Dover, suddenly discovering a purpose to go to England, and fearing

to be dissuaded by his people, gave them his faithful promise not to

go, but yet soon after he got board, and so departed. It was

time for him to be gone, for not long after a widow which kept in

his house, being a very handsome woman, and about 50 years of age,

proved to be with child, and being examined, at first refused to

confess the father, but in the end she laid it to Mr. Larkham.

Upon this the church of Dover looked out for another elder, and

wrote to the elders to desire their help.”

[40]

This allegation seems implausible because the first person of surname Nutter to arrive at Dover was Hatevil Nutter, who arrived in New England in 1630, settled at Dover Neck, New Hampshire, and died there in before 28 June 1675, when his will was proved. Thomas Larkham left Dover in 1642, long before there was a Widow Nutter living there.

In addition, the likelihood of a 50-year-old women conceiving a child seems relatively slim, even today.

Ironically, Hansard Knollys was also accused of immorality: “Mr. Knolles was discovered to be

an unclean person, and to have solicited the chastity of two maids,

his servants, and to have used filthy dalliance with them, which he

acknowledged before the church there, and so was dismissed, and

removed from Pascataquack. This sin of his was the more notorious,

because the fact, which was first discovered, was the same night

after he had been exhorting the people by reasons and from

scripture, to proceed against Capt. Underhill for his adultery.”

John Winthrop, 28.

[41] Mrs. G.H. Radford suggests

Larkham is probably referring to the biblical passage of Ezekiel

37:1-14. There are many online interpretations of this passage

that is believed to be a metaphor for the nation of Israel which was

exiled and scattered “as dry bones”, without hope or faith.

[42] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 162.

[43] The return from New England

was clearly a significant milestone in his life because he

referenced the date in several entries in his diary, mostly in

gratitude for the blessings he and his family had received since the

departure (all entries from Thomas Larkham and Susan Hardman Moore.

Page numbers in parentheses after entry dates):

August 1650

(46): “Nov. 12, 1642 I came from New

England Here followeth an accompt of what

God hath allowed me yearly since I came from N. England”

November 12, 1654 (100): “I call to mind with a humble and

thankful hearte that upon the 12th day of November 1642 I

left my house in the morninge and came down to the Mouth of the

River Paskataquacke in Newe England to come for England[.] I take

special notice of The special Goodnes of the Lord to me & mine for

these twelve yeares now fully ended this day November 12th

1654 beinge the Lords day which was on a Saturday that yeare I came

from New England.”

November 1655

(120): “The 12th of this

Moneth 1642 I left my house & familie in New England. It is

now full 13 yeares agoen, and the 17th day endeth the

first quarter of the 54th year of mine age, The day of

Queen Elizabeth coming to the crowne & c Greate have thy mercies

beene o Lord to this nation and to this poore sinfull worme in

particular” November 12, 1656

(138): “November. 12th 1656 I

call to mind this day, that 14 yeares agone On this day viz in the

yeare 1642 I left mine house in New England which was then on a

Saturday Now it is Wednesday my lecture day, on the Munday following

Novemb the 14th I set saile and so was brought to

England, where I have been protected preserved and provided for and

my family of whom I have had mine Eldest son taken away by death

whose son is livening with me, My other three (I hope George is

livinge)two of them viz Patience a Widdow & Jane married in

Tavistocke are living heere in Tavistocke. November 1657

(162): Novem. 14th 1642 I

came from New England And have beene since marvelously Cared for &

holpen by the Lord (My) father, to care for my famelie which (when I

left them) were as dry bones, & diverse yeares after; yet did the

Lord bring them altogether againe here in England.” November 1658

(188): “It is sixteene agone that I left

New England. Greate & marvelous o Lord have thy providences beene

over me and mine. I am as full as the moone and ready to burst

&c.” November 14, 1659

(211): “It is now 17 yeares since I left

my family in New England & came with my Eldest Son towards England.

O the mercies I have received! O the afflictions I have undergone! O

the providences God hath vouchsafed!” November 12, 1662 (258): “November 12th 1662 It

is full 20 yeares since I left my house in new England and came to

the havens mouth at Pascataquak and so tooke shipping & came thence”

[44] Mrs. G.H. Radford, 105.

[45] Tract in British Museum, p.

4.

[46] Mrs. G.H. Radford, 105.

[47] Mrs. G.H. Radford, 105.

[48] "Will of Richard Covert,

Merchant Tailor of East Greenwich, Kent." The National Archives. The

National Archives of the United KIngdom, n.d. Web.

<http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/SearchUI/Details?uri=D858234>.

Written August 28, 1638 and proved August 30, 1645.

[49] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 178, note 1.

[50] An interesting fact is that

while Larkham was in New England, he conveyed land to a man named

Joseph Miller. It’s not known if this is the same Joseph

Miller who married Larkham’s daughter.

History of the Town of Durham, New Hampshire provides

the following,: “The next lot northeasterly of

John Martin's was originally granted by the town to the Rev. Thomas

Larkham, between 1639 and 1642, who conveyed the same to Joseph

Miller. On the 21st of September 1647, Joseph Miller conveyed

to John Goddard the "house where Miller now liveth and five

acres of land," also twenty acres given by the inhabitants of

Dover, alias Northam to Thomas Larkham, "lyinge on the west

side of Backe River," also thirty acres of meadow ground lying

"on the westerlie side of the greate baye neere unto a cove

called the greate Cove," excepting ten acres given unto John

Ault by the said Thomas Larkham, also one hundred acres on the

easterly side of the said marsh ground given by Dover to said

Larkham.” See: Everett Schermerhorn

Stackpole, and Lucien Thompson, History of the Town of Durham,

New Hampshire : (Oyster River Plantation) with Genealogical Notes

[Volume 1]. (Durham: Published by Vote of the Town,

1913), 33.

[51] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore,

178.

“On this day also 1648. My poore daughter Miller was

safely delivered of her son Thomas at my house at Crediton alias

Kirton”

“Blessed be my God”

[52] Sydney Lee, 151.

[53] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 162.

[54] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 33.

[55] Dictionary of National

Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 32

[56] Susan Hardman Moore.

Pilgrims: New World Settlers & the Call of Home. (New Haven,

Conn.: Yale UP, 2007), 131.

[57] Susan Hardman Moore, 131.

[58] Susan Hardman Moore, 132.

[59] Tavistock Congregational

Church. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.tavistockurc.org/page19.html>.

[60] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 96.

[61] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 33.

[62] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 131. [63] In the late 1660s, Larkham’s grandson Thomas Miller went to Albemarle, Province of Carolina, where he exported tobacco to England and served as customs collector. He became (acting) Governor of Albemarle, Province of Carolina in 1677 until his government was overthrown in Culpeper’s Rebellion. After his return to England, he was appointed customs collector of Poole and later of Weymouth. By 14 May 1684, Miller had been removed from office and imprisoned for mishandling funds. His cousin, Tom Larkham, posted bond as surety for his cousin. When Thomas Miller died in prison, probably before 21 June 1685, Tom Larkham was arrested and imprisoned for the debt owed by his cousin Miller. Tragically, Tom Larkham also died in prison, sometime between 21 June 1685 when he wrote his will and 16 October 1685 when his widow made her first petition to the Customs Commissioners to be discharged of the bond given by her late husband as surety for Thomas Miller. This is documented through a series of petitions by Hannah Larkham, widow of Thomas Larkham (grandson of Rev. Thomas Larkham) from 1685-1688. In her petition, Hannah Larkham stated that her late husband, Thomas Larkham, had provided a surety bond to Thomas Miller “after his escape from the rebels in Carolina, having obtained an order for restitution which was prevented by the Earl of Shaftesbury, and being impoverished thereby ran in arrear to the King as customer of Poole and Weymouth, was arrested and died in prison…” Because Thomas Larkham posted bond for his cousin, he

“was

arrested for some arrears due by Miller and died in prison and that

his goods were seized and praying that she [Hannah Larkham] may

enjoy her goods, being all she has left, and proceedings be

suspended till Miller's plantations in Carolina can be regained for

satisfying the King's debt.” For a

more through overview and references, see:

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~sallycox/thomasmiller.html

[64] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 136.

[65] Sydney Lee, 151.

[66] Sydney Lee, 151.

[67] Sydney Lee, 151.

[68] Tavistock Congregational

Church. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.tavistockurc.org/page19.html>.

[69] Sydney Lee, 151.

[70] See

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Act_of_Uniformity_1662 and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Ejection

[71] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 258.

[72] Sydney Lee, 151.

[73] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 268. “Octob. 26th. T.

Miller my Grandchild came to me. My father shew what with him I

shall do, And still shew me the way that I

shall go.”

[74] Apparently the marriage was

not a success. In his bequest to his daughter Patience, he

states, “My apothecary ware & utensils …

[75] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 280.

[77] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 290, Note 2.

Fo. 47v gives a picture of Larkham’s fortunes after

the Five Mile Act (October 1665) came into force.

Under the act, a nonconformist like Larkham risked a fine of £40 if

he came within five miles of his former parish.

The Diocese of Exeter’s Episcopal Return in 1665 for Tavistock had

already listed

[78] The Earls of Bedford were of

the House of Russell and Members of Parliament for Tavistock. See:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Russell,_1st_Duke_of_Bedford

and

[79] Tavistock Congregational

Church. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.tavistockurc.org/page19.html>.

[80] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 304.

[81] Thomas Larkham and Susan

Hardman Moore, 305.

[82] Tavistock Parish Register.

[83] Edward Windeatt, "Early

Nonconformity in Tavistock." Report and Transactions of the

Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science, Literature,

and Art. Vol. 21. (Plymouth: W. Brendon & Son, George

Street, 1889.) 108.

[84] Thomas Lloyd Bush and Louise

Hornbrook Bush, “Transcript of the Will of Thomas Larkham, 1 June

1668”, The times of the Hornbrooks: Tracing a Family Tradition.

(Cincinnnati: T.L. Bush, 1977.) 55-57.

[85] Sydney Lee, 151. | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

Works Cited | ||||||||||

|

"Administration

Bond, Commission, Inventory, Will, 1640, Thomas Larkham, Linen

Draper, /Lyme Regis/Dorset."

Wiltshire Council.

Probate Records of the Court of the Dean of Salisbury. Web. 05 July 2014.

<http://history.wiltshire.gov.uk/heritage/getwill.php?id=100794>. P5/1640/40

Belknap, Jeremy,

and John Farmer. The History of New

Hampshire. Dover: S.C. Stevens and Ela &

Wadleigh, 1831. Print. Bolton, Charles

Knowles. The Founders: Portraits of

Persons Born Abroad Who Came to the Colonies in North America before the

Year 1701. S.l.: Boston Athenaeum, 1919.

Print. Calamy, Edmund,

Samuel Palmer, Thomas Gibbons, James Caldwall, and William Harris.

The Nonconformist's Memorial:: Being an Account

of the Ministers, Who Were Ejected or Silenced after the Restoration,

Particularly by the Act of Uniformity, Which Took Place on Bartholomew-Day,

Aug.24, 1662. Containing a Concise View of Their Lives and Characters, Their

Principles, Sufferings, and Printed Works.

London: Printed for W. Harris, No. 70, St. Paul's Church-Yard. Print. “England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975,” FHL

microfilm 917182. “England, Marriages, 1538–1973,” FHL microfilm

916934. Felt, Joseph B.

The Ecclesiastical History of New England

Comprising Not Only Religious, but Also Moral, and Other Relations.

Boston: Congregational Library Association, 1855. Print.

"Grant of

Administration, Will, 1640, Thomas Larkham, Linen Draper, /Lyme

Regis/Dorset." Wiltshire Council.

Probate Records of the Court of the Dean of Salisbury. Web. 05 July 2014.

<http://history.wiltshire.gov.uk/heritage/getwill.php?id=109704>. Reference

Number P5/13Reg/221B

Larkham, Thomas and Susan Hardman Moore.

The Diary of Thomas Larkham: 1647 - 1669.

Woodbridge: Boydell, 2011. Print. Larkham, Thomas,

and William Lewis. Diary of the Rev.

Thomas Larkham, M.A., Vicar of Tavistock, 1647-60.

Bristol: William F. Mack ..., 1888. Print. "Larkeham, Thomas

(1623 - 1641)."The Clergy of the Church

of England Database 1540-1835. Ed. Arthur

Burns, Kenneth Fincham, and Stephen Taylor. King's College London, Strand,

London WC2R 2LS, England, United Kingdom. Oct. 1999. Web. 05 July 2014.

<http://db.theclergydatabase.org.uk/jsp/persons/CreatePersonFrames.jsp?PersonID=71334>. Lee, Sydney, ed.

Dictionary of National Biography,

1885-1900, Volume 32.

New York: McMillan,

1892. Print.

Parish register transcripts, 1630-1837 Church of

England. Parish Church of Sandford (Devon) Parish register transcripts, 1538-1836 Church of

England. Parish Church of Northam (Devonshire). Radford, Mrs. G.

H. "Thomas Larkham."

Report and

Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science,

Literature, and Art. Vol. XXIV. Plymouth:

William Brendon and Son, 1892. 96-146. Print. Stackpole,

Everett Schermerhorn, and Lucien Thompson. History of the Town of Durham, New Hampshire:

(Oyster River Plantation) with Genealogical Notes [Volume 1].

Durham: Published by Vote of the Town, 1913. Print. The register of Bridekirk, 1584-1812 Church of

England. Parish Church of Bridekirk (Cumberland). The Western antiquary, Volume 8. Editor, William

Henry Kearley Wright. Publisher, Latimer & son, 1889. Original from,

Princeton University, 171. Transcripts of parish registers and Bishop's

transcripts, 1609-1837 Church of England. Parish Church of Highweek. "Will

of Richard

Covert, Merchant Tailor of East Greenwich, Kent."

The National Archives.

The National Archives of the United Kingdom. Web.

<http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/SearchUI/Details?uri=D858234>.

Written August 28, 1638 and proved August 30, 1645. Windeatt, Edward.

"Early Nonconformity in Tavistock."

Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of

Science, Literature, and Art. Vol. 21.

Plymouth: W. Brendon & Son, George Street, 1889. 108. Print. Winthrop, John.

Winthrop's Journal: "History of New

England,” 1630-1649. Ed. James K. Hosmer.

Reprint ed. The University of Michigan: C. Scribner's Sons, 1908. Print. | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Click here for an Adobe PDF version of the content on this page | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

The graphic on this page is a scan of the stencil,

Acanthus Border, The background paper on this page is from Ender Design's Realm Graphics collection. | ||||||||||

|

Last updated: Tuesday, December 20, 2022 09:47:33 AM | ||||||||||